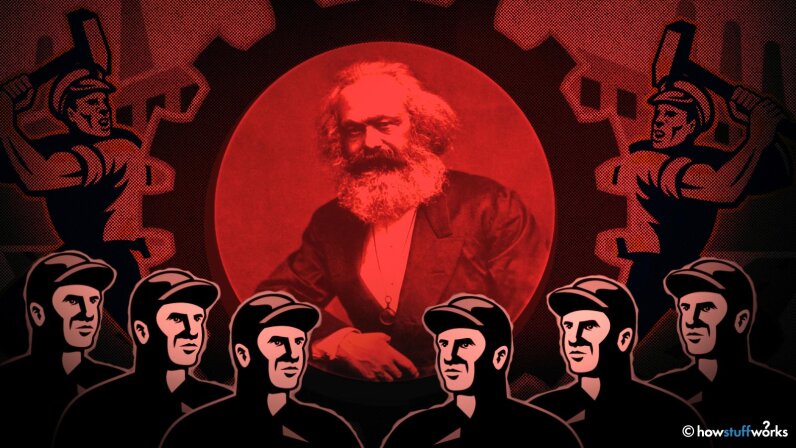

One quick glance at Karl Marx’s curriculum vitae says a lot. Economist, philosopher, journalist, sociologist, political theorist. Historian. Add to that socialist, communist (in the original meaning of the word) and revolutionary, and that’s just a start.

Karl Marx was one of the most respected minds of the 19th century. His meditations on how societies work, and how they should work, have informed and challenged humans for more than 150 years.

Yet to the uninitiated, Marx may be only a bushy-mugged symbol of revolution, the Father of Communism, the hater of capitalism. He is considered by many, especially in the West, as the man whose ideas spurred on authoritarian communist regimes in Russia, China and elsewhere.

That, again, is selling the man short because it’s not entirely right.

“Viewed positively, Marx is a far-seeing prophet of social and economic developments and an advocate of the emancipatory transformation of state and society,” writes Jonathan Sperber in “Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life.” “From a negative viewpoint, Marx is one of those most responsible for the pernicious and evil features of the modern world.”

If nothing else, Karl Heinrich Marx was a keen observer of the human condition. He was a deep thinker with bold ideas about how to make life better.

“Marx himself was first and foremost a kind of scientist,” says Lawrence Dallman, who teaches a course on Marx and philosophy at the University of Chicago and is the co-author of a chapter on Marx and Marxism in “The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Relativism.” “He was a student of reality. But he himself struggled throughout the course of his career with how exactly to put his ideas to politics.”

Growing Up Karl Marx

For the truly uninitiated it’s important to note that, despite his one-time lofty standing in the former Soviet Union, Marx was born in Trier, in the Kingdom of Prussia, in 1818. That’s what’s now known as the Rhineland area of Western Germany. After the failed German revolution of 1848, Marx fled to London, where he died in 1883. He’s buried beneath a large tomb in London’s Highgate Cemetery.

Marx grew up privileged, the son of well-off and liberal parents, in an ancient town that had been racked for decades before his birth by war and revolution. That upheaval — cultural, religious, and political — shaped his parents and was a big part of young Marx’s upbringing.

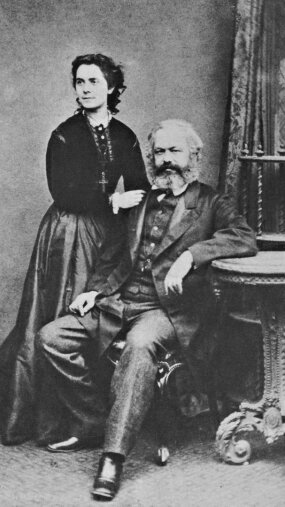

Later, Marx attended universities, studying law and philosophy, where he became engaged to (and later married) a Prussian baroness, Jenny von Westphalen. The two met in their hometown of Trier, while teenagers. It was while studying philosophy and law that Marx was introduced to the works of German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whose ideas he used to later form his take on communism.

Marx began a career as a journalist in his early 20s, writing for radical newspapers in Cologne and in Paris. Throughout, he consorted with other liberal-minded philosophers and, by his mid-20s, met and collaborated with one of the major influences in his life, Friedrich Engels. It was Engels who convinced Marx that society’s working class would be the instrument to fuel revolutions and bring about a more fair and just society.

In 1848, the two published a pamphlet that would be the basis for a new political movement: “The Communist Manifesto.”

In 1883, after Marx’s death, Engels summed up the main idea in The Communist Manifesto:[T]hat economic production, and the structure of society of every historical epoch necessarily arising therefrom, constitute the foundation for the political and intellectual history of that epoch; that consequently (ever since the dissolution of the primaeval communal ownership of land) all history has been a history of class struggles, of struggles between exploited and exploiting, between dominated and dominating classes at various stages of social evolution; that this struggle, however, has now reached a stage where the exploited and oppressed class (the proletariat) can no longer emancipate itself from the class which exploits and oppresses it (the bourgeoisie), without at the same time forever freeing the whole of society from exploitation, oppression, class struggles.

“Marx was always concerned to understand the real underlying causes of social phenomena, the events and institutions that shape the social world,” explains Dallman. “Marx wanted to dig down beneath the appearances and see what was really going on. Early on in his career, he thought that the best arena to do that in was philosophy. And then as time went on, he transitioned more into the social sciences.

“What’s most important about Marx is that he very much had an engineering mentality about society. He wanted to know what makes it work and how, if we want to change it, do we change it. What are the levers that we have to pull?”

Communism vs. Capitalism

Marx’s 1847 economics work, “Capital. A Critique of Political Economy,” a takedown of capitalism that decried the exploitation of the working class, crystallized a debate — one that continues today — between the West’s ruling social and economic theory, capitalism, and Marx’s idea of communism. To many, it’s a fight that pits rich versus poor; bourgeoisie versus proletariat; ruling class versus workers. It is even more than that to those who debate it: It’s right versus wrong, an argument about the best path to a perfect society.

But that, of course, is criminally simplistic and doesn’t get Marx’s thinking right.

“Above all else, the association that people have with Marx, that he’s some utopian, pie of sky, dreaming up a perfect world that is free of all the nastiness we live in now … really, that couldn’t be further from the truth,” Dallman says. “As I said, Marx had a kind of engineering mindset. He was, probably of all the major figures in the history of political thought, the most practical, the most realistic. He was the most concerned with what is really possible in the real world.”

What Marx defined as communism — boiled down, a society that produces goods only for human need, not for profit, and in which there is no master-slave/royalty-peasants/owner-worker relationship (and therefore no need to overthrow anybody) — certainly clashes with the materialism of capitalism. But it’s a long way from what many see as communism, too.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, and later under Joseph Stalin’s reign, some of Marx’s ideas (along with those of Vladimir Lenin) were used to build a new empire. Millions were killed along the way. Similarly, millions died in China under the rule of Mao Zedong’s communist party.

“It’s hard to even talk about what Marx thought of communism without dragging in all the weight from Soviet Russia and communist China,” Dallman says. “And, obviously, a lot of people hold Marx responsible for that.”

Clearly, authoritarian rules like Stalin’s and Mao’s were not what Marx had in mind. It’s important to note, too, that Marx did not hate capitalism. Far from it. He actually saw some virtue in the system. He saw it as a necessary precursor to communism. He envisioned some of the technological challenges — automation unseating workers, for example — that are true today.

“Marx was very impressed with the progressive character of capitalism. By forcing people from all different walks of life into the same workplaces, capitalism breaks down the old divides between communities,” Dallman says. “And so things like race and gender and religion divide people less, the more people are forced to see each other as equals in the workplace.”

Marx recognized and marveled at the economical and technological growth that capitalism spurs, and saw it as an improvement from previous societies. Later in life, Dallman says, Marx suggested a growth in capitalism might be a way to move toward communism, instead of all-out revolution.

But he still saw communism — with no master-slave dynamic — as the end goal.

In that way, and in others, Marx’s idea of communism was far from the atrocities committed in the name of communism elsewhere. And his ideas are still, perhaps strangely to many, a beacon in a search for a better way of life. In that, a practical man and deep thinker of the 19th century still has relevance in today’s world.

“Marx was so committed to giving a rational criticism of everything. Not just the enemy, but to himself and everything,” Dallman says. “He was willing to criticize the old modes of life and show how capitalism improved on them, but he was also willing to criticize capitalism and show how we could foresee improvement coming in the future. That is still a hopeful vision.”